Not a cut-and-dry summary of the book (I already knew a lot of the underlying concepts, so I didn’t take notes on anything I knew). It’s a mix of (mostly illegible) notes on the book + my thoughts on some specific things, and it’s not even in chronological order because all of my post-its got mixed up :(.

Readers of “Thinking: Fast and Slow” should read the book as a subjective account by an eminent psychologists [sic], rather than an objective summary of scientific evidence. Moreover, ten years have passed and if Kahneman wrote a second edition, it would be very different from the first one. Chapters 3 and 4 would probably just be scrubbed from the book. But that is science. It does make progress, even if progress is often painfully slow in the softer sciences.

General vibes: I thought I’d already known how fallible our brains were, and I mostly read this book in hopes of improving my meta-thinking, but this made me a lot more pessimistic. The extent to which cognitive biases affect us seems almost fantastical.

- System 1 vs System 2

- System 1 is fast, intuition-based, immediate, effortless

- System 2 is lazy, requires effort, checks the answers of system 1

- The brain is an association machine

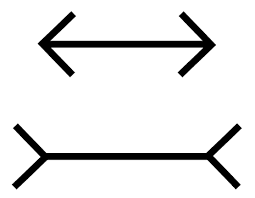

- You can’t not see the Muller-Lyer illusion. The best you can do is be aware of major fallacies and hope to avoid them in important situations (aka the point of this book).

- We have a limited budget of cognitive attention. In a real sense, you are literally paying attention.

- Intuition is only developed through deliberate practice (when something from System 2 enter System 1).

- We like thinking of everything causally and seeing agents everywhere. In fact, the reason the book talks about systems 1 and 2 is because we like thinking of things in the form of agents w/ motives and traits. This could actually be a sneaky good way of improving explanations.

- Not falling prey to biases strongly correlates with self-control because you need to have as strict of a System 2 as possible.

- Substitution Bias

- We deal better with averages than sums. “System 1 represents sets by averages, norms, and prototypes, not by sums.”

- If few broken pieces of china are added to an otherwise good china set, it loses value in individual comparisons, although of course that shouldn’t be the case.

- Scope Insensitivity

- Most people can differentiate well between 10 birds dying and 100 birds dying.

- Halo Effect

- First impression matters. We tend to substitute new opinions about people based on the easier question of evaluating them on a previous opinion.

- Intensity Matching

- We’re usually good at generalizing → express how tall Sam would be if he was as tall as he was smart

- We deal better with averages than sums. “System 1 represents sets by averages, norms, and prototypes, not by sums.”

- The Priming Effect

- Cognitive Ease

- Wisdom of crowds only works well when observations are independent and their errors are uncorrelated.

- Relevant for Superforecasting + How to make good predictions + Organizational Culture.

- When you’re gathering opinions about something, do an anonymous async survey before an open discussion in a meeting. Otherwise observations will stop being independent, and errors will be repeated because people will tend to moderate their beliefs to agree with each other. culture

- Relevant for Superforecasting + How to make good predictions + Organizational Culture.

- The Anchoring Effect

- Risk

- Loss Aversion

- We tend to avoid losses over achieving equivalent gains. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint.

- WYSIATI

- Cognitive Biases in Mental Search

- It’s easy to favor unlikely explanations because they have better stories.

- Always bias towards simplicity

- Affect Heuristic

- The tendency to believe that the positions we support are costless, and the positions we are against have no benefits.

- Research shows that students of psychology don’t learn well when presented with surprising statistics. They internalize much better when surprised by individual examples.

- “Subjects’ unwillingness to deduce the particular from the general was matched only by their willingness to infer the general from the particular.”

- “But even compelling causal statistics will not change long-held beliefs or beliefs rooted in personal experience. On the other hand, surprising individual cases have a powerful impact and are a more effective tool for teaching psychology because the incongruity must be resolved”

- Regression to the mean

- “correlation and regression are not two concepts—they are different perspectives on the same concept. The general rule is straightforward but has surprising consequences: whenever the correlation between two scores is imperfect, there will be regression to the mean.”

- Echoing advice from Superforecasting, we tend to greatly overvalue causal base rates and greatly undervalue statistical base rates

- Very simple algorithms can often outperform expert intuition

- Taming intuitive predictions

- How would you estimate the college GPA of an early reader?

- Start with an estimate of the average GPA.

- Determine the GPA that matches your impression of the evidence (in other words, do some intensity matching).

- Estimate the correlation between reading and GPA.

- If the correlation is .30, move 30% of the distance from the average to the matching GPA.

- When can you trust expert intuition?

- When the intuition is born in Environments that are good for deliberate practice

- You can practice often

- Tight feedback loops

- Easy way to distinguish between success and failure

- High-signal feedback

- Example: You can trust the intuitions of good chess players because

- They practice often

- Chess has tight feedback loops

- There’s a relatively easy way to distinguish between success and failure

- There’s relatively high-signal feedback (mentors, coaches, other players can provide this)

- When the intuition is born in Environments that are good for deliberate practice

- Planning Fallacy

- Theory-induced blindness

- “once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws. If you come upon an observation that does not fit the model, you assume that there must be a perfectly good explanation that you are somehow missing.”

- 3 Principles that govern how you value outcomes and make decisions

- You evaluate based on a reference point (your anchor). Fluctuations in states of wealth aren’t seen purely for what they are, but rather as wins and losses from the perspective of your anchor.

- Diminishing sensitivity

- Loss Aversion

- Loss aversion means that “the disadvantages of a change loom larger than its advantages, inducing a bias that favors the status quo.”

- Not just in people, but in organizations. Those who lose out because of a change will generally be more passionate than those who win.

- Based on the above two:

- If you have a precious ticket to a game, you will have a higher selling price because you will be considering the pain of losing the ticket and experience loss aversion.

- Certainty effect: You will pay a premium to increase certainty to 100%.

- Possibility effect: You will pay more than expected value to reduce small risks (if you take them seriously).

- The FourFold Pattern:

- Gains + High Probability = Risk Averse

- 95% to win $10,000

- Gains + Low Probability = Risk Seeking

- 5% to win $10,000

- Losses + High Probability = Risk Seeking

- 95% to lose $10,000

- Losses + Low Probability = Risk Averse

- 5% to lose $10,000

- “Many unfortunate human situations unfold in the [losses + high probability] cell. This is where people who face very bad options take desperate gambles, accepting a high probability of making things worse in exchange for a small hope of avoiding a larger loss. Risk taking of this kind often turns manageable failures into disasters. The thoughts of accepting the large sure loss is too painful, and the hope of complete relief too enticing, to make the sensible decision that it is time to cut one’s losses. This is where businesses that are losing ground to a superior technology waste their remaining assets in futile attempts to catch up.”

- Gains + High Probability = Risk Averse

- Rare Events

- Will always be either virtually ignored or overweighted

- Vivid imagery makes you less sensitive to probability.

- “1 in 100” carries more weight and draws more attention than “1%.”

- “The probability of a rare event is most likely to be overestimated when the alternative is not fully specified.”

- It’s easier to imagine the success of a plan than to imagine failure because there are only a few concrete paths to success, but many different situations where failure could happen. This is why the idea of a premortem is so useful.

- To be resistant to loss aversion, and end up losing out overall, Internalize the mantra that “you win a few, you lose a few” and make the decision based on what you think would be best if 100s of alternative yous exist.

- If you’re an individual investor, make long-term investments and follow your investments on a quarterly basis instead of following daily fluctuations.

- Sunk-Cost Fallacy

- Do what gives you the best chances for the future irrespective of the past.

- People tend to bias towards inaction

- they expect to feel more regret from outcomes that are produced by action than from inaction

- Preference Reversals

- Your morals intuitions in specific cases aren’t consistent with the beliefs you have when your reflect about morality because of WYSIATI. Factors that you believe shouldn’t have an impact on your decision (and don’t when you compare different cases) actually do when you’re making daily decisions on individual cases.

- Frames

- People prefer a surgery that is framed as having a 90% survival rate, than one that is framed as having a 10% mortality rate.

- “Your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself.” The broader quote: “Now that you have seen that your reactions to the problem are influenced by the frame, what is your answer to the question: How should the tax code treat the children of the rich and the poor? Here again, you will probably find yourself dumbfounded. You have moral intuitions about differences between the rich and the poor, but these intuitions depend on an arbitrary reference point, and they are not about the real problem. This problem—the questions about actual states of the world—is how much tax individual families should pay, how to fill the cells in the matrix of the tax code. You have no compelling moral intuitions to guide you in solving that problem. Your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself…framing should not be viewed as an intervention that masks or distorts an underlying preference. At least in this instance…there is no underlying preference that is masked or distorted by the frame. Our preferences are about framed problems, and our moral intuitions are about descriptions, not about substance.”

- Well-being

- Contrast between the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self”

- The correlation between the happiness of the two selves is about the same as the correlation of the heights of parent and child.

- Peak-end rule: Your feelings about an episode are generally an average of the peak emotion and the last emotion.

- Duration neglect: You won’t factor in the length of an episode much when evaluating how you feel about it.

- These two lead to bad decisions. You may choose to repeat an episode that has more overall pain but a lower peak and a better end,

- As a doctor, should you give preference to the experiencing self or the remembering self? Should you prefer a surgery that minimizes suffering in reality while worsening the memory of the experience? Should you prefer a surgery that increases suffering in reality but leaves a better memory of the experience?

- These two lead to bad decisions. You may choose to repeat an episode that has more overall pain but a lower peak and a better end,

- Life as a story

- We care about evaluating lives as stories.

- We feel bad learning that a dead man’s partner was cheating on him without his knowledge even though he died happy.

- We feel bad for a scientist whose life-defining discovery is proved false after they die, even though that wasn’t part of their experience.

- We care about “living up to XYZ’s legacy” and “upholding XYZ’s legacy.”

- We care about evaluating lives as stories.

- Ways to improve experience well-being

- Switch from passive leisure to active leisure

- As societies (small changes can have large cumulative effects)

- Improve transportation

- Increase availability of child care

- Improve socializing opportunities for the elderly

- Something will only make you happy when you think about it. Attention is the medium through which we experience life.

- Goods are overrated: You’ll eventually stop thinking about your car while driving or about your new house while living in it.

- Experiences will require your attention every time. A book club will occupy your attention every meeting. Playing guitar will require your attention every practice session.

- “The remembering self’s neglect of duration, its exaggerated emphasis on peaks and ends, and its susceptibility to hindsight combine to yield distorted reflections of our actual experience.”

- Because of the above + attention, people might give different ratings on life satisfaction surveys than during daily sampling surveys. When they’re taking a life satisfaction survey, they will think about their recent promotion, their new car, the lovely weather, and their house (or their injury) but they won’t pay much attention to these things in daily life.

- Contrast between the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self”

- How much freedom should people have?

- “freedom has a cost, which is borne by individuals who make bad choices, and by a society that feels obligated to help them.”

- Libertarian Paternalism

- The state nudges people to make decisions that serve their long-term interests. Good decisions are the default path, but people have the option to opt-out. Their freedoms aren’t infringed upon in any meaningful way.

- “Humans, unlike Econs, need help to make good decisions, and there are informed and unintrusive ways to provide that help.”

- “[Decision makers] will make better choices when they trust their critics to be sophisticated and fair, and when they expect their decision to be judged by how it was made, not only by how it turned out. ”